U.S. Trade Deficit Widens Despite Trump’s Tariffs

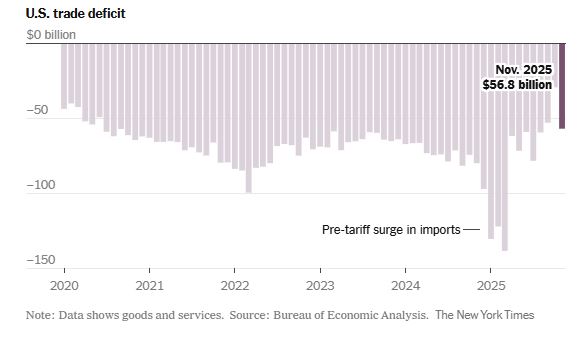

The monthly trade deficit and imports rebounded in November after shrinking significantly in prior months, new data show.

The U.S. trade deficit in goods and services rebounded to $56.8 billion in November, rising 95 percent from the previous month as President Trump’s tariffs continued to cause huge fluctuations in trade, according to data from the Commerce Department released on Thursday.

Exports fell 3.6 percent in the month, to $292.1 billion, led by declining outbound shipments of gold, pharmaceuticals, consumer goods and crude oil. Imports rose 5 percent in November, to $348.9 billion, as Americans bought foreign pharmaceuticals as well as equipment to fill new data centers. The combination pushed up the monthly trade deficit, the gap between what the United States imports and what it exports.

The data reflected some of the intense volatility that has resulted from the president’s decision to impose steep taxes on imports over the past year. The trade deficit had fallen significantly in prior months, seemingly accomplishing a major goal for Mr. Trump, who views that metric as a sign of economic weakness. The October trade deficit was the lowest monthly figure recorded since June 2009.

But much of that drop was the result of temporary fluctuations in trade in certain products, like gold, which investors have sought out as a haven amid tariff-related turmoil. Economists have cautioned against a single-minded focus on the trade deficit, saying that it can move for a wide variety of reasons, and that last year was particularly volatile when it comes to trade.

In the early months of Mr. Trump’s presidency, companies rushed to bring goods into the country before tariffs took effect, causing imports and the trade deficit to spike. After Mr. Trump announced sweeping global tariffs in April, shipments of imports fell back. Other types of products, like pharmaceuticals and semiconductors, have also seen import surges and declines as the president announced, imposed and changed tariffs throughout the year.

The tariffs have also shuffled trade with various countries. From January to November, the goods trade deficit with China was only $189 billion, less than the United States’ trade deficit with the European Union, and only slightly larger than America’s trade deficit with Mexico.

While importers have changed the timing of their shipments to avoid tariffs, when added together trade still approximated normal levels. Last year through November, the overall trade deficit was still up 4.1 percent from the previous year.

Exports for the first 11 months of 2025 were 6.3 percent higher than the previous year, while imports were 5.8 percent higher. Data for December and the full year will be released next month.

The question for economists now is where trade goes from here, and if the president’s policies continue to lower imports or the trade deficit in the long term.

Diane Swonk, chief economist at KPMG, said the increase in the trade deficit from October to November was the largest monthly increase on record, apart from the surge last January when Mr. Trump returned to office. The trends were driven by the trade in gold, as well as pharmaceuticals, a sector that was “was incredibly volatile in 2025,” she said.

Eugenio Aleman, the chief economist for Raymond James, an investment bank, said the increase in the monthly deficit was “larger than expected” and would bring down projections for U.S. economic growth in the fourth quarter. Net imports are subtracted from economic growth figures to avoid double counting, so the drop in the trade deficit in prior months had increased estimates for U.S. gross domestic product.

Tariffs could undergo more changes in the weeks to come. The Supreme Court is set to rule soon on the legality of many of the tariffs that Mr. Trump issued using a 1970s emergency law, though the Trump administration has said that any levies that are struck down will be quickly replaced using other legal workarounds.

The administration has used the emergency law to impose tariffs on nearly all countries and added more levies to products and sectors it deems important to national security, including steel, copper and upholstered furniture. As of January, the U.S. effective tariff rate had climbed to nearly 17 percent, the highest level since 1935.

———————————————————————–

Ana Swanson covers trade and international economics for The Times and is based in Washington. She has been a journalist for more than a decade.